Relevant to this is time complexity and more generally decidability

Space complexity shares many of the features of time complexity and serves as an additional dimension with which to classify problems

Definition: The space complexity of a deterministic Turing machine that halts on all inputs is the function , where is the maximum number of tape cells that scans on any input of length

We say runs in space

If is a nondeterministic Turing machine, we define its space complexity to be the maximum number of tape cells that scans on any branch

Definition: We define space complexity classes as the set of languages decided by an space deterministic Turing machine and as the set of languages decided by an space nondeterministic Turing machine

Space is more powerful than space because it can be reused

For example, we can reason that can be reasonably solved in linear space, even though it’s an -complete problem

An important example we will look at is

We can decide the complement in linear space by nondeterministically reading in inputs (this is the maximum before it will repeat) and updating the possible states of our NFA accordingly

Savitch’s Theorem: For any ,

Our regular way of simulating an NTM is not sufficient, because it could potentially use space

So how does one prove this? Let decide nondeterministically in space

We construct a deterministic TM deciding using the procedure , which tests whether a configuration of can yield another within a specified number of steps

works by recursively checking for each using space whether and

We modify to clear the tape on accept and move the head to the leftmost cell, so that there is a single accept state, and select a constant such that has no more than configurations using tape

“On input : Output the result of ”

This is correct, but how much space does our method use? Well each level of the recursive stack must store which takes space, and there are levels, coming out to

(A technical difficulty is that this requires knowing the value of , but we can actually determine this manually by simulating on each value until we know it has rejected, and this is fine from a space standpoint)

Definition: is the class of languages decidable in polynomial space on a deterministic Turing machine,

We can also define , but as we showed

So by Savitch’s theorem, since is in we know it is also in

We can easily reason and

Similarly, a TM that uses space cannot have more than configurations before repeats, so

In summary,

Of these, the only certainty is , but general consensus is that these containments are all proper

PSPACE-Completeness

has an analog to NP-Completeness

Definition: A language is PSPACE-complete if is in and every in is polynomial time reducible to

If is not necessarily in then we call it PSPACE-hard

The reason we use time reducibility instead of space reducibility is simply because time is much more limiting and a better representation of what we aim to achieve with completeness

To give an example, we introduce a more general type of Boolean formula which uses quantifiers in prenex normal form, known as quantified Boolean formulas (like )

When each variable is within the scope of a quantifier, the formula is fully quantified, sometimes called a sentence

Theorem: is -complete

We can’t use the exact same method as with the Cook-Levin theorem, since the height of the tableau would be exponential and therefore cannot be produced in polynomial time

Instead, we use a technique related to our Savitch’s theorem proof

First, it’s apparent that we can specify a algorithm that decides

Now let be a language decided by a TM in space for some constant

For our reduction, we design a formula parameterized as where is true if can go from to in at most steps (for convenience a power of ), and then our final reduction uses where for a constant

Like before, we define to encode that either or follows from in a single step of , using the same ideas as in the Cook-Levin theorem

For , we construct recursively

A naive approach might try , but this still gives an exponentially large formula

A working recursive definition that reduces the size is

This is possible because we can define in terms of Boolean operators, and so this definition properly adds space for each division of , yielding a formula of size

PSPACE-Complete Problems

A game is loosely defined as a competition in which opposing parties attempt to achieve some goal according to prespecified rules

Games are closely related to quantifiers, which we will demonstrate with an artificial formula game

Let be some quantified Boolean formula in prenex normal form

Two players take turns selecting the values of the variables ; Player A selects values bound to quantifiers and Player E selects values bound to quantifiers

Player A wins if , the part of the formula without the quantifiers, is false, and Player E wins if it is true

We say that a player has a winning strategy for a game if that player can always win the game

Player has a winning strategy in the formula game associated with

Theorem: is PSPACE-complete

This is clearly true because Player E wins precisely if , that is the process of choosing variables in order is exactly the condition under which a quantified variable is true or not

Let’s look at another kind of game based on geography, the children’s game in which players take turns naming cities that begin with the last letter of the previous city, until there are no option available

In generalized geography, we take an arbitrary directed graph with a designated start node

Player I has a winning strategy for the generalized geography game played on graph starting at node

Theorem: is PSPACE-complete

First, we can solve with a recursive brute-force algorithm, which only requires the space of the recursion stack, i.e. linear space

To map the formula game to , we use a diamond construction somewhat reminiscent of the proof of HAMPATH’s NP-completeness, but much simpler

We first map to a formula whose quantifiers start and end with and strictly alternate between and , which we can easily do with dummy variables

Then, the geography game that simulates goes in two parts

- Players alternate selecting edges that represent the values of

- Player A chooses a clause, and then Player E wins if they can choose a satisfied variable

In other words, no polynomial time algorithm exists for optimal play in generalized geography unless , which is even stronger than

It would be nice if our methods could be applied to games like chess, however conventional board games have a finite state space and are thus unsuitable for asymptotic analysis

The Classes L and NL

If we modify our computational model slightly, we can meaningfully consider sublinear space bounds

We consider a two-tape model, where one tape is limited to the size of the input and is read only

With this model, we can exclude the size of the input from our space analyses

Definition: is the class of languages that are decidable in logarithmic space on a deterministic Turing machine

Definition: is the class of languages that are decidable in logarithmic space on a nondeterministic Turing machine

We consider logarithmic space because it is much smaller than linear but still solves useful problems, and happens to be robust under machine model and input encoding changes

One way of understanding the power of logarithmic space is with indices/pointers, which are logarithmic on the input size

Example:

We can’t use our zig-zag approach, crossing off 0s and 1s, since that requires space

Instead, we run through the input and use two binary counters to keep track of the number of 0s and 1s, and compare the counters at the end

In binary, each counter uses only logarithmic space, so this algorithm runs in space, and

This is a very intuitive algorithm, but using counters is quite difficult to demonstrate explicitly in the Turing machine model

Example: PATH

We can solve this in by only keeping track of the current node, and nondeterministically moving to the next one, until we either find the target or use steps

So is in

Our earlier claim that space bounded Turing machines also run in time is no longer true for very small space bounds, because our definitions have changed

We can analyze sublinear spaces with an updated definition of machine configurations

Definition: If is a Turing machine that has a separate read-only input tape and is an input, a configuration of M on w is a setting of the state, the work tape, and the positions of the two tape heads, but not the input

If runs in space and is an input of length , the number of configurations of on is , since each configuration stores the working tape and the location of the pointer on the read-only tape

So our bound accounting for sublinear spaces is

Similarly, we can slightly modify the proof of Savitch’s Theorem to account for the updated definition, and the result is the same

NL-Completeness

Surprise! also has an analogue to NP-Completeness

Everything is about the same, however since all problems are solvable in polynomial time, we use a new kind of reducibility

Definition: A log space transducer is a Turing machine with a read-only input tape, a write-only output tape, and a read/write work tape, where the output tape cannot move leftward, and the work tape may contain symbols

A log space transducer computes a log space computable function where is the string remaining on the output tape after halts when it is started with on its input tape

Language is log space reducible to language , written , if is mapping reducible to by means of a log space computable function

Definition: A language is NL-complete if and every in is log space reducible to

Theorem: If and , then

A naive approach would be directly mapping to , however could be too large for the log-space bound

Instead, we trade time for space and recompute from scratch individual symbols whenever requested, such that only a single symbol of needs to be stored at any point

Corollary: If any -complete language is in , then

Theorem: is -complete

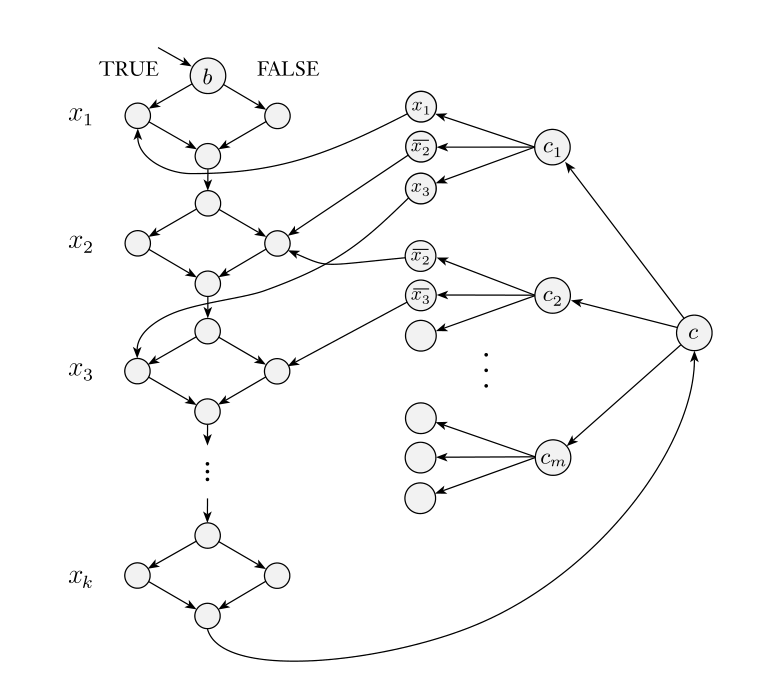

We map a log space Turing machine to a graph , where the nodes represent configurations of on , with an edge from to if is a possible next configuration of starting from

We modify to have a unique accepting configuration, designated as

This machine can operate in log space by sequentially going through all possible strings of length and outputting them if valid configurations, and likewise for edges

Corollary:

This follows simply from the fact that a Turing machine using space runs in , so log space reducers run in polynomial time, and therefore every language in is polynomial time reducible to , which is in

Log space reducibility is actually adequate for most reductions, and it terms out is enough for reductions like the reduction to , which can be useful in understanding relationships like

NL Equals coNL

and are generally believed to be different, and our intuition would expect this fact to carry over to

Theorem:

The essence of the proof is showing that is in , and therefore the rest of

While this algorithm is not tricky to verify, I personally found the nondeterministic reasoning used to construct it tricky to fully grasp

We first calculate , the number of nodes reachable from

This cannot be done directly in logarithmic space, however we can use an iterative method

We calculate from by going through all nodes of and checking if any node reachable in steps has an edge to

How do we make sure we’ve checked every node reachable in steps? Nondeterminism doesn’t help us for this, and we can’t just store the nodes reachable in because of the space constraint

We solve this by nondeterministically selecting a path to every node in , and incrementing an auxiliary variable

If we find then great, but otherwise we check if and reject otherwise

Now that we have our value , we can nondeterministically select paths to each node (excluding ) and accept only if we reach nodes

Since we exclude from this search, reaching nodes means is not reachable, which concludes the algorithm

Since we only use counter variables, this algorithm runs in logarithmic space, and therefore

Our present knowledge of the relationships among complexity classes is

The strict subset of in is shown here

Most researchers conjecture that all these containments are proper, but we do not have the tools to prove much about it