NP-completeness is an important advance in the question of P vs NP

Some problems can be formally linked to the rest of , meaning a solution to these problems implies a solution to the rest of

This is very important practically, because it means we have a means of proving a problem is probably unsolvable in polynomial time

The theory of NP-completeness starts with the satisfiability problem

A Boolean formula is an expression involving Boolean variables and operations, and is satisfiable if some assignment of variables makes the formula evaluate to

Theorem:

How is this true? We use the concept of reducibility to prove this theorem

Definition: A function is a polynomial time computable function if some polynomial time Turing machine exists that halts with just on its tape, when started on any input

Definition: Language is polynomial time (mapping) reducible to language , written if a polynomial time computable function exists, where

We call a polynomial time reduction

This is an analog to mapping reducibility, and it’s useful because it establishes shortcuts for proving membership to , and therefore

Theorem: If and , then

As an example, we first introduce a slight variation on the satisfiability problem

A literal is a Boolean variable or a negated Boolean variable, a clause is several literals connected with s, and a Boolean formula is in conjunctive normal form (called a cnf-formula) if it comprises of clauses connected with s

A cnf-formula is called a 3cnf-formula if all clauses have three literals

Theorem:

We convert a 3cnf-formula into a clique problem by creating a node for each item in all clauses and making an edge two nodes if they are in different clauses and are not negations of each other; then, we test for a -clique

This tells us that if is solvable in polynomial time then so is , even though they are quite different looking problems

Definition: A language is NP-complete if is in and every in is polynomial time reducible to

If is -complete and , then

If is -complete and for in , then is -complete

This is fascinating, but requires us to have a single -complete problem before we can connect other problems

Theorem: is -complete

This is not a simple proof, since it requires showing that any language in is polynomial time reducible to , a fact that looks ridiculous at first glance (at least to me), but makes more sense when you consider that Boolean operations are the basis for electronic circuitry

The reduction is fairly simple conceptually but requires dealing with many details

Proof:

To start, is trivially in

Let be a nondeterministic Turing machine that decides in time

A tableau for on is an table whose rows are the configurations of a branch of on

Each row starts and ends with and we place the head’s state at its location on the tape, offsetting the rest of the tape (due to this configuration, we technically assume the machine decides in )

A tableau is accepting if any row of the tableau is an accepting configuration, so the problem of determining whether accepts amounts to determining if an accepting tableau for on exists

Let , where is the state set and is the tape alphabet

For each and , we have a variable

Each of the entries of the tableau is called a cell, and its value is designated through the variable which takes on the value

Let’s now produce a formula that corresponds to an accepting tableau for on , which will take the form

We first guarantee that each cell has a single value set, through the expression

Then, we explicitly require the first row to be the starting configuration with

We require an accepting configuration

Our final formula is the most complex, guaranteeing that configurations are legal by scanning through the cells with a window, which is enough context to guarantee transitions are valid

If the top row of the tableau is the start configuration and every window in the tableau is legal, then each row of the tableau is a configuration that legally follows the preceding one

We omit the precise definition and write

” is a legal window” is a well-defined boolean expression dependent on the Turing machine’s transition function

‘s total size is , which shows we can define in polynomial time

Thus, we can reduce any Turing machine on into a problem, which proves the Cook-Levin theorem, showing is -complete

Corollary: is -complete

We note that we can use some Boolean algebra to create from the proof in 3cnf, by distributing when necessary and splitting larger clauses like into

NP-Complete Problems

For reasons not well understood, most naturally occurring -problems are either in or -complete

Proving a problem is -complete is useful because it tells you a better solution does not exist (for all intents and purposes)

To do this, we look for structures in a language that can simulate the variables and clauses in Boolean formulas, sometimes called gadgets

Our previous theorem now tells us is -complete

A vertex cover of an undirected graph is a subset of the nodes where every edge of touches one of the nodes

Theorem: - is -complete

For each variable in , we produce an edge connecting two nodes, labeled and

For each clause in , we produce a node for each variable in the clause, all connected to each other, and all connected to their corresponding variable node as specified above

has nodes, where has variables and clauses, and we let

We create a cover from a solution of by taking the true literal variables in the cover, and excluding one true literal in each clause triplet

A little thought shows that we can also do the inverse, so - polynomially reduces to and is therefore -complete

The takeaway in this example is that we are looking to simulate variables and clauses in the problem we’re looking to reduce

Theorem: is -complete

We look to show that for any 3cnf-formula , we can construct a directed graph with two nodes, and , where a Hamiltonian path exists between and is satisfiable

where each is a literal or for

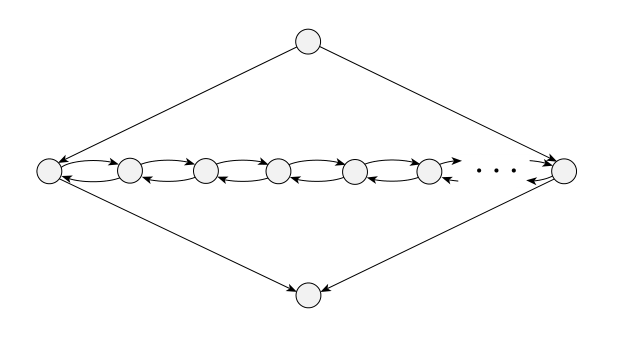

The graph looks like a sequence of diamonds representing each variable, where starts at the start of the diamond of and ends at the end of the diamond of

Each diamond allows for two possible paths that snake through, going from the start to the left represents and going to the right represents

Hence, with this construction, a path encodes a selection of or for each

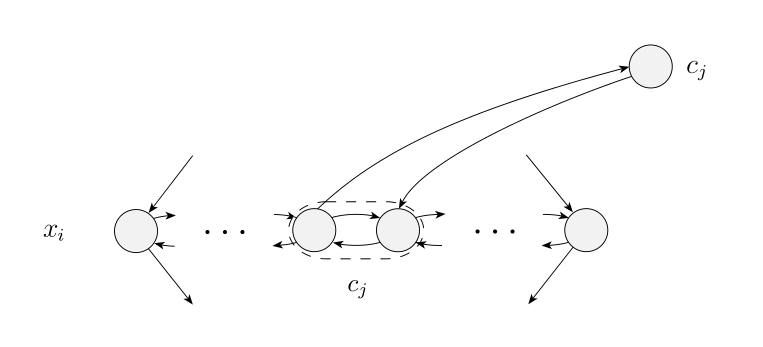

Now how do we encode the clauses? The key is that in the center of each diamond we hold intermediate nodes, corresponding to pairs for each clause and separators between these pairs

To the side of our diamonds, we have one node per clause

These nodes are hooked up to the diamonds such that they can be entered and exited along a path encoding only if the clause contains , and they can be entered and exited along a path encoding only if the clause contains

Thus, a satisfiable expression can be converted into a path quite simply, by snaking through the variables according to the selections of and attaching each clause to the path at the first variable that satisfies that clause

The separators in between clause pairs guarantee that any Hamiltonian path must be “normal”, i.e. it follows our expected construction and does not take any shortcuts

Theorem: is -complete

Our construction before no longer works because our connections between a clause and a variable can be satisfied whether a path selects or

Instead, we make a reduction that takes a general directed graph with nodes and and constructs an undirected graph with nodes and , such that has a Hamiltonian path from to has a Hamiltonian path from to

We replace each node of by a triple of nodes in , except for and which are replaced with and respectively

Then, we add in if in

It’s clear that a Hamiltonian path in corresponds to a Hamiltonian path in , if we follow the “intended” directions

And furthermore, the only way to form a Hamiltonian path in is following the intended direction, because we are forced to hit the middle nodes and therefore must transition from to until we get to

Theorem: - is -complete

We reduce to an instance of -

Each number in the problem has a digit for each variable and a digit for each clause

Each and transforms to a number with a in the corresponding digit and a in each clause that it takes part

In addition, each clause transforms to two identical numbers with a in the corresponding clause

Then, the problem is to sum to a number with all s in the digit portion and all s in the clause portion