Alan Turing proposed the Turing machine model in 1936. A Turing machine is similar to a finite automaton but with unlimited and unrestricted memory. A Turing machine can do anything a real computer can do.

The Turing machine model uses an infinite tape as its unlimited memory, along with a tape head that can read and write a finite symbol set, and move around on the tape. It also tracks state and can reject or accept immediately, ending the process.

The fact that this is general computing model is not super intuitive.

Example: Recognize

We use English to describe the concept of our algorithm

“On Input string :

- Zig-zag across the tape to corresponding positions on either side of the # symbol to check whether these positions contain the same symbol. If they do not, or if no # is found, reject. Cross off symbols as they are checked to keep track of which symbols correspond.

- When all symbols to the left of the # have been crossed off, check for any remaining symbols to the right of the #. If any symbols remain, reject; otherwise, accept.”

Definition: A Turing machine is a 7-tuple, , where are all finite sets and

- is the set of states,

- is the input alphabet not containing the blank symbol ,

- is the tape alphabet, where and ,

- is the transition function,

- is the start state,

- is the accept state, and

- is the reject state, where .

We compute as follows: Initially, receives its input on the leftmost squares of the tape, while the rest of the tape is filled with . Computation proceeds according to the transition function. If the head moves past the left-hand end, it stays in place. Computation continues until or is reached, or never halts.

We often write the configuration of the machine as to indicate that the tape is and the head is at with state

We say one configuration yields another, which is a deterministic operation. A Turing machine accepts input if a sequence of configurations exists where is the start configuration of on input , yields , and is an accepting configuration.

As with other kinds of machines, denotes the language recognized by

Definition: A language is Turing-recognizable (recursively enumerable) if some Turing machine recognizes it

Turing machines can either accept, reject, or loop. A Turing machine can fail to accept an input by either rejecting or by looping. Turing machines that never loop are called deciders. A decider that recognizes a language is said to decide it.

Definition: A language is Turing-decidable (recursive) if some Turing machine decides it

In general, we use high level descriptions of Turing machines, descriptions that are precise enough and understandable. However, we are always able to translate a high level description into a more mechanical formal counterpart.

Example: that decides

Concept:

Repeatedly divide the number of 0s in half until there’s an odd number remaining. Accept if there’s only a single 0, reject if there’s more.

High level description:

- Sweep left to right across the tape, crossing off every other 0.

- If in stage 1 the tape contained a single 0, accept.

- If in stage 1 the tape contained more than a single 0 and the number of 0s was odd, reject.

- Return the head to the left-hand end of the tape.

- Go to stage 1.

Formal description:

,

- ,

- , and

- .

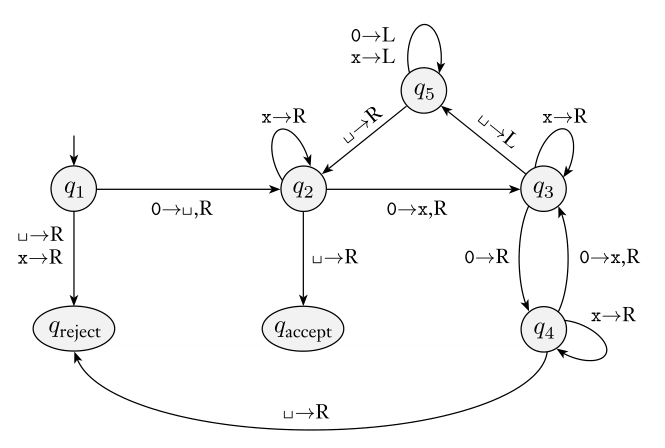

- We describe with a state diagram below

- The start, accept, and reject states are , and , respectively.

This is a somewhat optimized formal description. It initially blanks out the first 0, meaning we are essentially recognizing . Each iteration recognizes an odd number of 0s, crossing off half of them (rounded up, which will be a power of 2 on a valid string). On a valid string, we can keep doing this until we’ve crossed out everything. On the last iteration, only one 0 will be crossed out, so .

We often omit explicit reject transitions to simplify things (in which case lacking a transition is a rejection). Similarly, in my high level descriptions, if I say to do something and that thing cannot be done, we implicitly reject.

Example: recognizes .

- Scan the input from left to right to check that is a member of

- Return the head to the left-hand end of the tape

- For each a, scan to the right until a b occurs, and alternate crossing off c’s for each b (marking each b to track which have been observed), and then restore the marked off b’s

Example: recognizes

- Place a “mark” on the leftmost tape symbol, which is a

- Mark the next (if there is none, means accept)

- Zig-zag to compare the two marked strings (marking observed symbols and restoring afterwards)

- Move the right marker to the next string, if it’s the last string then move the left marker forward one and the right marker to the one after the left (this effectively enumerates through the comparisons)

- Go to stage 3

Note the idea of marking a symbol, which means using an alternative symbol

Variants

Alternative Turing machine definitions are called variants. They all have the same power, which is an invariance referred to as robustness. However they can improve readability and expressibility.

Definition: A multitape Turing machine has individual tapes, with modified transition function

This can be expressed with a regular Turing machine ,

- puts its tape into a format representing all tapes with heads marked

- To simulate a single move, checks each head to identify the proper transition, and then makes a second pass to update each tape

- If ever moves a head to the end of its tape, shifts over the tape contents to make room

Definition: A nondeterministic Turing machine acts as a tree whose branches correspond to different possibilities, with

We can simulate this on a deterministic TM. The core idea is using a breadth-first search to explore the possibilities. We store the original input tape, a simulated tape, and an address tape, which stores an address of our decisions. We repeatedly increment the address and simulate the machine on the address.

Definition: An enumerator is a Turing machine with an “attached printer”. It enumerates a language if any string in that language will eventually be outputted.

Theorem: A language is Turing-recognizable some enumerator enumerates it

This theorem is quite intuitive. One trick that helps prove it is noticing how one can give the effect of running in parallel on all possible input strings by running for steps on for all (as in incrementing)

The key feature of a Turing machine is its unrestricted and unlimited memory. All models (including programming languages) that meet the most reasonable requirements for memory access share this equivalence.

This has an important implication; We have a well-defined class of algorithms

Algorithms

Algorithms have had a long history in mathematics but were not defined precisely until the twentieth century. Before then, mathematicians relied on intuition but lacked a deeper understanding.

Hilbert proposed the problem of recognizing polynomials with integral roots, with the assumption of a solution. We now know this is algorithmically unsolvable. However, intuition would not tell us this.

The Church-Turing Thesis connects Church’s formal -calculus and Turing’s machines. These are the tools that can give insight into precise notions of decidability.

With the understanding (and intuition) that Turing machines capture all algorithms, we are no longer interested in the low level descriptions at all

The formal description spells out the Turing machine’s states

The implementation description uses English to describe how we maneuver the head around the tape

The high-level description ignores the machinery entirely and merely describes the “algorithm”

Our high-level descriptions describe steps as stages and indent to indicate block structure. We describe inputs as encodings of our objects. Our implementation description is similar but must describe the operation with regards to the Turing machinery and the structure of our input encoding.